August 16, 2018

“The Train Seemed to Take Forever to Come, a Trick of Perception”

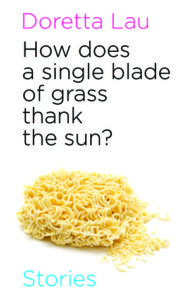

Yesterday, I woke up with an intense urge to re-read one of my favourite short stories of all time, “Writing in Light” from Doretta Lau’s strange and memorable collection How Does A Single Blade Of Grass Thank The Sun? I first read this book in 2014, and I remembered that I’d enjoyed “Writing in Light” for the narrator’s singular voice and for Lau’s deft weaving of fictional storytelling elements with art theory. At the time, I was new to my process of art autodidacticism (still am, probably always will be) and she helped pique my interest in both narrative craft and art history.

“Writing in Light” follows a young woman on a New York City subway ride from her apartment (where her ex thinks perhaps an episode of Law and Order was filmed?) to a small art gallery (that the narrator had read about months before in the The New Yorker and remembers only that the owner resisted the exodus to Chelsea). As she journeys, we learn about her encounters with a particular artist, Jeff Wall, and some of his works, namely Double Self Portrait, Ventriloquist at a Birthday Party October 1947, and The Destroyed Room. We learn how her curiosity about and study of staged photography has helped her settle some conflicts in her own mind about performance and appearance–what sort of work should she, a descendent of manual labourers, do? What sort of social life should she, a self-proclaimed awkward introvert, have?

We are aware throughout the piece that the narrator is, like Wall, also constructing an image, a life. We sense she does this not in order to ‘impress’ or ‘cope,’ but in order to ‘pass,’ unnoticed, akin to how a Jeff Wall image can, at a cursory glance, pass as documentary photography instead of what it actually is: meticulously planned, intensely staged, the final image selected from what could be hundreds of different shots from different angles.

I’m reminded of this passage from the essay “Lightbox Paradox” by my friend and photographer David Evans, about the impact the advent of conceptual photography had on the medium in general: “Photographs are very disturbing. When we want the truth from them they deceive us, and when we want beauty, they can be cold and objectifying. People are not always happy to be confronted with the unvarnished truth, especially those for whom the truth might prove embarrassing. Photographs makes us a little uncomfortable because they are machine made, beyond human control. The vast majority of photographs, (snapshots of family, friends, and pets, travel souvenirs, and of course, selfies) are essentially unmediated. Advertising photography, and cinema is, of course, entirely staged. For the most part, I would argue, people are able to discern the difference quite easily, just as, face to face, people are able to distinguish a forced smile from a genuine one.”

I think here, Evans gives “people” a little too much credit. Perhaps he pays enough attention to know when someone is forcing a smile (and he does), but I would argue (and maybe Lau’s narrator would, too), that for the most part, we don’t.