September 21st, 2018

Yesterday, listening to The Daily while walking my dog, I cried, as I often do, thanks to the highly-skilled storytelling and editing abilities of The Daily‘s producers and the emotionally manipulative score that plays lightly under Michael Barbaro’s dulcet murmurs of encouragement for his interview subjects. At its most hardened, The Daily covers political scandals; at its softest, the victims of a natural disaster or war or abuse. Yesterday’s episode, called “A High School Sexual Assault,” did both. As I so often do, I let my mind wander throughout the introduction, only tuning in seriously when the interview subject began reading signatures from her high school yearbook–a great hook. So, I missed the fact that the woman talking was Caitlin Flanagan, writer for The Atlantic and proponent of the idea that the #MeToo movement has gone too far.

I found the episode remarkable in that it was entirely devoted to this woman’s recollection of her experience fighting off a teenage boy who tried to rape her. He’d driven her to a beach and forced himself on her to the point where she had to scream and shove and punch to get him off. A fragile girl having just moved to a new town and already struggling with depression, this attack sent her over the edge and she attempted suicide. Flanagan reminds the listener in an admonishing tone that she wasn’t a strong girl who’d became suicidal after the attempted rape; she was a barely holding herself together girl who became suicidal after the attempted rape. It’s a distinction that asks the listener to extend her the allowance of context that she herself might not be willing to extend to others.

The story turns when Flanagan reveals that the apologetic yearbook signature she’s read at the beginning of the episode was in fact from her attacker, and that two years after that initial written apology came an even better apology, in person and with his own tears. These two apologies combined showed Flanagan that he 1) recognized the seriousness of his offence, 2) understood the impact it could have had on her and 3) was genuinely sorry. These apologies helped her heal. These apologies are what’s missing for Dr. Christine Blasey Ford.

Anyone with a cursory understanding of trauma knows that much of the emotional injury of abuse comes when the abuser will not acknowledge the impact of her actions. Studies show that medical malpractice lawsuits decrease when the physician apologizes for her mistake. It’s all connected to the witness theory, and it’s why we have truth and reconciliation hearings, and it’s why when teachers make bullies apologize to their victims, it is less about punishing the bully and more about supporting the victim. A victim needs to feel heard in order to begin healing.

I’m happy Flanagan told her story. She’s the perfect victim. She fought off her aggressor and went on to become successful. At the most difficult parts of her story, her voice shook and threatened to break into tears, which Barbaro interpreted as the lasting impact of the initial trauma. Yes, I nodded as I walked Chispi through the downpour. Those are her body memories coming up. Good things she’s got them under control. Good thing she’s stronger and can acknowledge the pain but quickly move past it to focus on the healing. In her yearbook, her attacker had written, “I know you will succeed because you are smart.” And Flanagan exclaims to Barbaro, “I did succeed…because I am smart!”

Eight months ago, in “The Humiliation of Aziz Ansari,” Flanagan wrote the following:

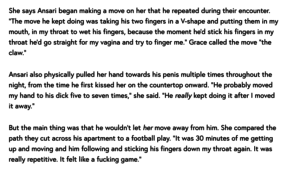

Here are some of the details of Grace’s account:

While I don’t right now agree that Grace’s story should have been published, I also believe Ansari is guilty of a physical or sexual assault of some kind, and at the very least of sexual harassment. If a woman moves her hand away from your dick, you don’t keep grabbing it and putting it back. That is coercive. That is physical coercion.

I think Flanagan read that Babe piece and felt anger toward Grace; why didn’t she handle these physical intrusions the way she’d handled them as a teenage girl in the 1970s? Grace should have screamed, shoved and punched her way out of Ansari’s apartment. After all, there’s no distinguishing context to extend to Grace. For some, shoving a horny teenage boy off of you in a car on the beach is the same as shoving a millionaire celebrity off of you in his Manhattan flat. For some, the 1970s are the same as 2018: it’s still up to the woman to stop the assault, not up to the man to recognize her as a human being and not a “flesh vase for his dick flowers.”